By Catherine Wecksell

With an increasing demand for online learning, instructional designers are adapting existing online instruction programs to create remote learning. TV legends like Fred Rogers, LeVar Burton, and Bob Ross provided effective distance learning before it became widespread. What techniques do these three TV hosts offer instructional designers for effective workplace learning today?

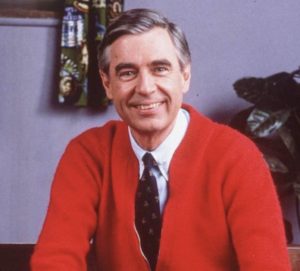

Fred Rogers was more present virtually than most people manage to be in person.

Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood ran from 1968 to 2001, one of the longest-running children’s PBS series. Mr. Rogers spoke directly to children, validating their feelings and helping them name, face, and understand their emotions. Many have applied his methods to adult contexts such as leadership, HR, and pedagogy.

Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood ran from 1968 to 2001, one of the longest-running children’s PBS series. Mr. Rogers spoke directly to children, validating their feelings and helping them name, face, and understand their emotions. Many have applied his methods to adult contexts such as leadership, HR, and pedagogy.

Mr. Rogers engaged children with open-ended questions, asking them about their experiences and urging them to draw upon prior knowledge. He presented models and examples in “The Land of Make Believe,” encouraging children to connect these to their own experiences. Jack Mezirow established transformative learning theory in 1978, with the concept that the learner’s critical self-reflection can transform the learner’s perspective (Mezirow, 2009). Mezirow grounded his concept in the foundational theory of constructivism, based on the idea that people actively create their knowledge and understanding. Your reality is determined by your experiences as a learner. Learner-centered instruction further acknowledges learners’ differences, shifting the planning and control of learning from the instructor to the learner.

Mr. Rogers exemplified this principle, to the extent one can on TV. While the children couldn’t direct the content on the episodes (the true learner-centered approach), his show included enough other content (such as visiting factories and interviewing guests) that the emotional instruction was an “offering” rather than a lesson to be imparted. Mr. Rogers’ gentle guidance and questioning put the learner at the center of the experience. He sang these words at the end of each episode: “I’ll be back, when the day is new, and I’ll have more ideas for you… You’ll have things you want to talk about… and I will, too.”

LeVar Burton helped a generation become self-directed learners.

Actor LeVar Burton (Roots, Star Trek the Next Generation) hosted Reading Rainbow on PBS from 1983 to 2009. This beloved show encouraged a love of reading by exploring various topics related to a featured children’s book. Segments approached books from many directions, from character interviews and celebrity appearances to visiting the book’s setting. Reading Rainbow earned over 200 broadcast awards, including a Peabody and 26 Emmy Awards. There are now interactive Reading Rainbow apps and video field trips for the iPad® and Kindle®.

Actor LeVar Burton (Roots, Star Trek the Next Generation) hosted Reading Rainbow on PBS from 1983 to 2009. This beloved show encouraged a love of reading by exploring various topics related to a featured children’s book. Segments approached books from many directions, from character interviews and celebrity appearances to visiting the book’s setting. Reading Rainbow earned over 200 broadcast awards, including a Peabody and 26 Emmy Awards. There are now interactive Reading Rainbow apps and video field trips for the iPad® and Kindle®.

LeVar taught around a subject, adding context by introducing related topics. Interdisciplinary learning combines learning objectives and methods from more than one branch of knowledge to focus on a central theme, issue, or problem. Interdisciplinary learning transfers knowledge gained in one discipline to another and deepens learning.

Even with LeVar’s acting skills, he didn’t read or dramatize the book. Learners were encouraged to read the books themselves. Sometimes people misunderstand self-directed learning (SDL)—it is not about working alone. SDL means a learner sets and often measures their own learning goals and progress. Another critical part of SDL includes sharing the learning process with peers and collaborating. LeVar would say, “But you don’t have to take my word for it…” Children would then come on screen and make book recommendations to each other.

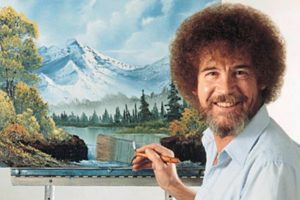

Bob Ross taught skills one happy cloud at a time.

Bob Ross hosted The Joy of Painting, another PBS television show that aired from 1983 to 1994. Bob Ross demonstrated with each brushstroke how to paint landscapes in oil. Many enjoyed watching him demonstrate specific landscape painting techniques by showing how to create integral elements, such as the sky, trees, and “happy clouds.”

Bob Ross hosted The Joy of Painting, another PBS television show that aired from 1983 to 1994. Bob Ross demonstrated with each brushstroke how to paint landscapes in oil. Many enjoyed watching him demonstrate specific landscape painting techniques by showing how to create integral elements, such as the sky, trees, and “happy clouds.”

Observational learning is a subset of social learning theory and describes learning from watching and mimicking others’ behaviors. Techniques of observational learning include modeling, shaping, and chaining. Observational learning is most common with children as they tend to copy adults naturally. However, on-the-job skills are also learned via observational learning.

People often develop new skills by shadowing. An example of this is having a new hire observe a more experienced employee on the job. Video tutorials and recorded screen captures are also observational learning.

Bob Ross’s consistency and demonstration of skills set his instruction apart. His impeccable planning of the show achieved this consistency. Bob planned each word and made three copies of his paintings for each show. Careful planning, prepping, and storyboarding are also vital to quality workplace learning and facilitation excellence.

Employ Learner-Centered techniques as Mr. Rogers did:

- Build open-ended questions into the learning experience.

- Have the learner draw upon their own experience and construct their own meaning.

- Allow the learner to direct and take ownership of what is learned.

Encourage Self-Directed and Social Learning the same way as LeVar Burton:

- Encourage independent exploration of content by providing ample resources and materials.

- Build peer collaboration with discussion boards and communities of practices.

- Use an interdisciplinary approach to teach many job functions around a single example.

Create consistent Observational Learning in the same way Bob Ross did:

- Include demonstrations or simulations.

- Provide guides to support workplace shadowing.

- Prototype your learning assets.

Mr. Rogers’ listening and empathy were profound, allowing children to feel acknowledged without even being in the same room. LeVar Burton stimulated self-directed and social learning. Bob Ross led learners through excellence in observational learning. They engaged learners without being able to see or get feedback from them. You can use the same learner-centered, self-directed, social, and observational approaches employed by these famous TV educators to engage remote workplace learners today.

REFERENCES

Mezirow, Jack (2009). An overview on transformative learning. In Knud Illeris (ed.), Contemporary Theories of Learning: Learning Theorists — In Their Own Words. Routledge.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Photos of Fred Rogers and LeVar Burton were obtained from Wikimedia commons, who provide the sourcing and copyright information for them at the following links:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:LeVar_Burton_July_2017.jpg

https://simple.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fred_Rogers#/media/File:Fred_Rogers_and_Neighborhood_Trolley.jpg

®Bob Ross name and images are registered trademarks of Bob Ross Inc. © Bob Ross Inc. Used with permission.