By: Adele Sommers

Imagine you’re attending an exciting, high-value conference on how to be a more effective communicator and leader. The many distinguished presenters tout impressive careers and credentials.

Each acclaimed speaker shares a compelling message illustrated by colorful charts, graphs, and figures.

Given this impressive backdrop, is there any reason to doubt a word the speakers are saying?

The trouble is, even in these settings, wise and learned people sometimes spread bogus, debunked, or dubious information. And when we hear something that sounds intriguing and plausible from someone we like and respect, we often can’t wait to share it with others!

Let’s examine two popular myths so you can recognize them the next time you see them — and avoid passing them along to other people as gospel.

Myth #1: The “7%-38%-55% rule”

Myth #2: The “10-20-30-50-70-90% theory”

Myth #1: The “7%-38%-55% rule”

This rule claims that when we listen to people speaking, we derive their meaning as follows:

- 7% from their spoken words

- 38% from their tone of voice, and

- 55% from their body language

In other words, the rule says we supposedly gain very little understanding (only 7%) from the verbal part of a message, which involves the words and phrases used. Instead, we gain most of the meaning (the remaining 93%) from the nonverbal cues given off by the speaker, such as his or her tone of voice and body language.

Why is that a myth?

Although this rule does have some validity, it has been incorrectly interpreted to apply to everything — including factual information. If the rule actually did apply to factual information, we’d have very little reason to listen to someone’s words to understand the meaning behind them, such as during a lecture. To make sense of the lecture — even if it were delivered in a foreign language — we could primarily focus on the speaker’s gestures and tone of voice, and mostly ignore the words themselves.

Therefore, the common belief that the “7%-38%-55% rule” applies to every type of information is false. It’s a gross mischaracterization of the research conducted by Dr. Albert Mehrabian in the 1960s. Dr. Mehrabian’s research was not about communicating ideas in general. As explained here, his findings pertained only when people were expressing their feelings and attitudes in an ambiguous way.

How so? When people say one thing about their emotions but convey something very different through their tone of voice and body language, it’s confusing and makes us wonder what’s really true. For example:

Verbal: Richard says, “I feel very relaxed and comfortable with you.”

Nonverbal: Richard looks anxious, stares downward, and appears withdrawn.

So, what should we believe in this case? Should we believe the verbal or the nonverbal aspects of Richard’s message?

If you said the nonverbal aspects, you were right. Whenever people express their emotions ambiguously, Mehrabian found that listeners focus on the nonverbal cues (tone of voice and body language) more than on the spoken words. That’s the correct interpretation of Mehrabian’s “7%-38%-55% rule”!

For an excellent illustration of this myth in action, watch this short video: Busting the Mehrabian Myth

Myth #2: The “10-20-30-50-70-90% theory”

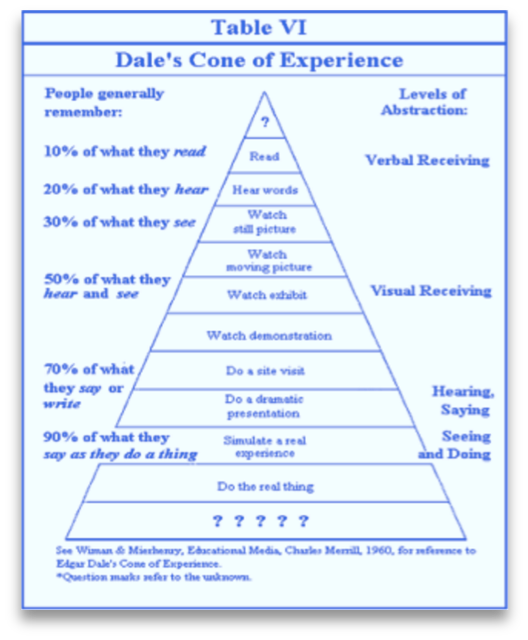

This theory proposes that certain kinds of learning activities are more effective than others in helping us remember something new. For example, the theory suggests that we’ll remember:

- 10% of what we read

- 20% of what we see

- 30% of what we hear

- 50% of what we see and hear

- 70% of what we say and write, and

- 90% of what we say and do

Why is that a myth? Although the basic idea sounds fairly reasonable, there seems to be no scientific evidence to back it up. It also has some other glaring problems — here are just two of them…

First, the percentage figures are too neat and tidy to be scientific. Valid research studies are unlikely to produce results that are cleanly rounded to the nearest multiple of 10 (20%, 30%, 40%, and so on), as noted by Dr. Will Thalheimer, who has carefully critiqued this myth.

Further, presenters often tailor their numbers (as well as their categories) to mirror the subject they’re talking about, without citing any credible scientific data. In other words, they fabricate their figures to match their message!

Second, the model represents a gross generalization about learning. Learning depends on many factors. So, we need to be very careful about attributing learning to activities that aren’t clearly defined (and these activities aren’t clearly defined). Because the meanings aren’t clear, the related assumptions don’t hold water, either.

Once you start asking a few questions like these, the theory begins to fall apart:

- What’s the difference between “seeing” and “reading”? Why would we remember more from seeing?

- Do we really learn more from “hearing” something spoken than from “reading” the same material? Doesn’t reading allow us to go back several times to revisit and ponder an idea, unlike hearing?

- What exactly does “saying and writing” refer to? Does it mean that we would write out a section of text while speaking it out loud? Wouldn’t that be distracting for some people?

- When we learn something by “doing,” does that imply that we’re being given timely and meaningful feedback by an instructor or coach that would tell us whether we’re doing it correctly? We don’t know.

So, how did this theory originate?

The model itself has evolved over time, appearing in many different forms since the 1960s or earlier.

Many variations have surfaced as bar charts, circle diagrams, pyramids, and cones — and all contain invented numbers, categories, or both.

One example is the “Cone of Experience,” attributed to Edgar Dale, who wrote about audiovisual media in 1946.

Dale’s “cone,” however, did not include any percentages. So, like many examples attributed to Dale, the one pictured has totally made-up information.

In summary, it’s tempting to jump on the bandwagon and adopt new ideas from people you respect and admire. But some of what masquerades as wisdom is really misleading — or pure bunk — passed along by respectable people who never fully fact-checked their references. So, don’t be fooled! Keep an eye out for myths like these and be sure to dig deep into any sources of information that you pass along!

Adele Sommers has spent over two decades helping firms boost their profitability through improved human and business results. She designs award-winning e-learning, instructor-led courseware, and blended training for organizations in a variety of industries, including financial and insurance services, manufacturing, trust building, project management, leadership development, presentation design, process improvement, quality assurance, and various technology-related fields.

Adele holds a Doctorate in Education with a focus on Human Performance Technology, as well as a Certificate in Human Performance. She is the president of Business Performance Inc., a consultancy she launched in 2006. She has also served as president of the San Luis Obispo Technical & Business Communicators (formerly, the San Luis Obispo chapter of the Society for Technical Communication) since 2002. More information about her professional work resides at LearnShareProsper.com.